Visual Artist

I am a visual artist and a B.F.A. graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. These recent, graphite dust drawings- and probably everything I've made- are part of my Alaskan upbringing.

A person's memories of childhood can shift a lot over time. They can be verifiable, but drawing could be distinct from the reliability of memory and how memory returns to us, maybe surviving the transition.

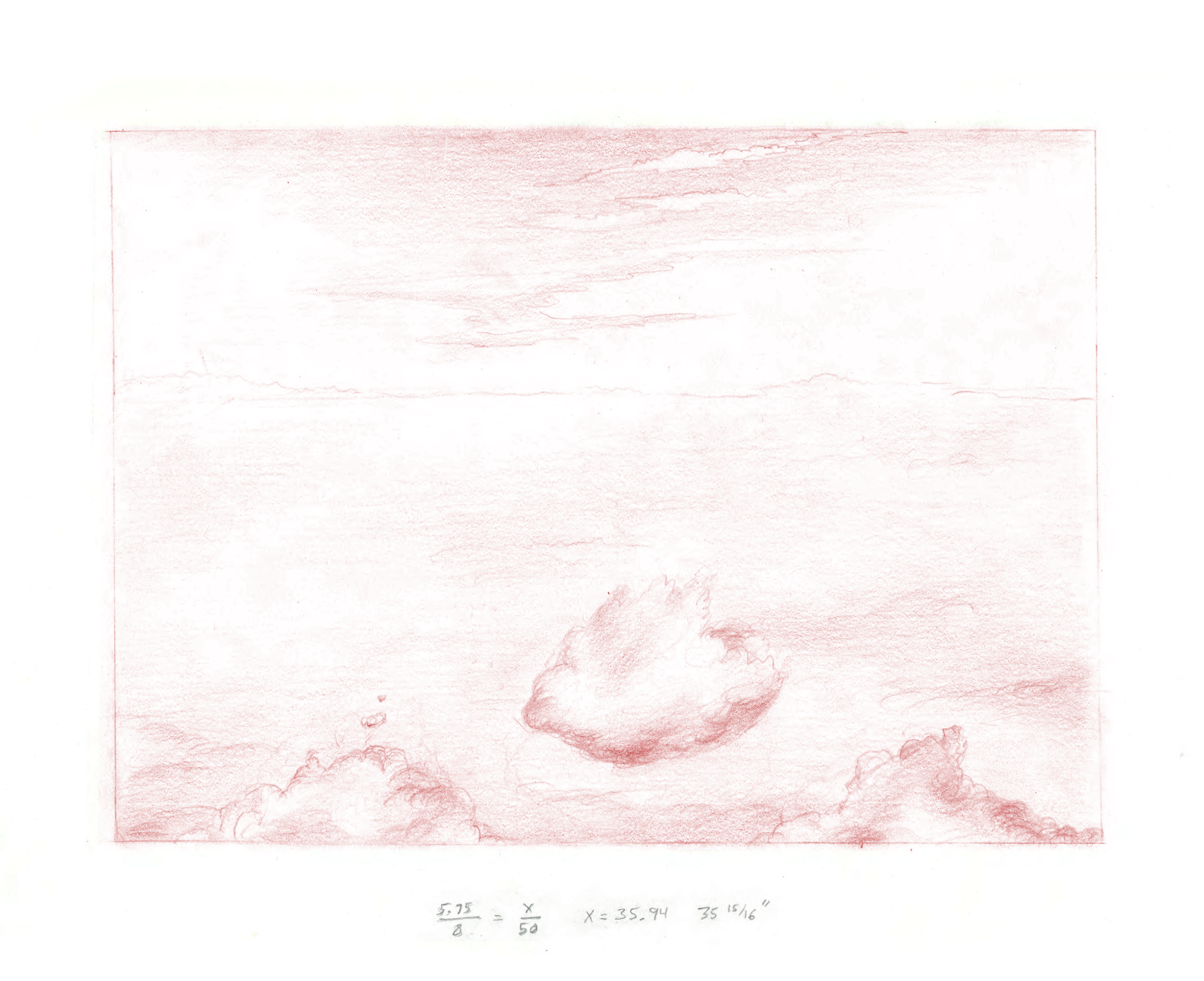

A lot of my drawings start as studies. The vignette for Division is color pencil.

One of the things that happened was pareidolia, or seeing patterns and meanings that don't exist. From study to large scale the center cloud became an eye. It followed that it could be made a pair, so I added one on the left side.

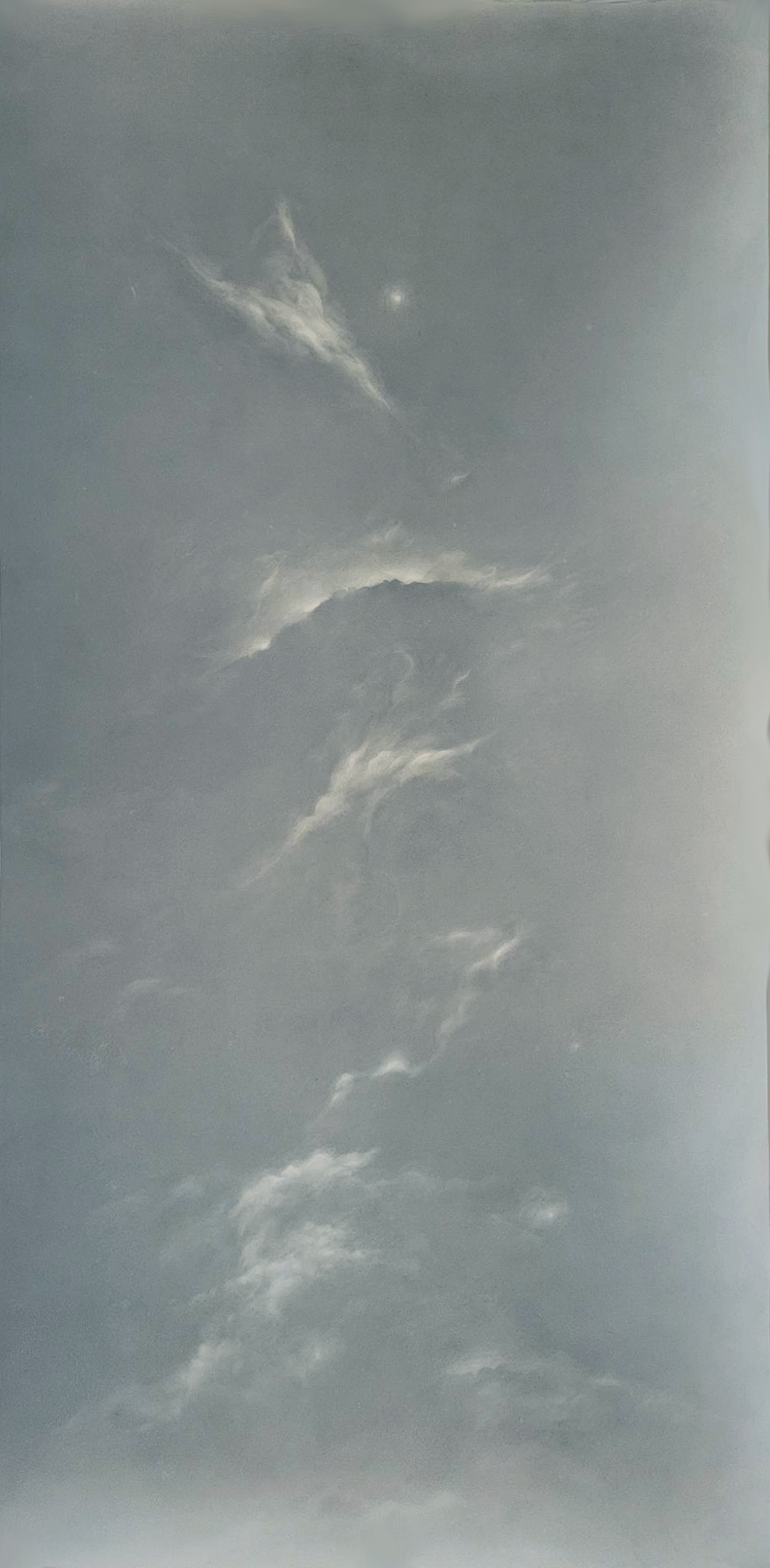

Division. 2015

Landscape can be about a specific place and to me places have the potential to create people and shape them. Alaska may have carried into the drawing an ethereal feeling that wouldn’t haven’t been there before. In those layers of experience that feeling happened before the first drawings.

The irrational and the imagery of children's books can cross over into many artists’ drawings:

Dawn Detail

Sometimes the eraser moves over the gesso, revealing glitters of light on the surface.

The glitters of light and diffused mistiness feel like video feed. If it were audible, maybe it would sound like cassette tape fuzz. When it looks like you're viewing a place through a filter, distant in place or time, for me that is ideal. It can be said the unknown is the most important parts of any artistic practice, like film, music or drawing, and layers of time and drawings that look like they’re falling apart.

Record and Forget

Drawing is a kind of reportage. Something is observed and is sometimes reported again. Even if we don't know what the event's meaning was- if it's recorded- it can still be reviewed and allowed reflection in a distant, hopefully more understanding future. We could be collecting memories for a distant, unforeseen review and though they may not be verifiable, they may meet more than just one end-point. You can change what they mean.

To conclude, the landscape of Alaska was a place that I could see, whether from ground or from an airplane. Landscapes are immediately palpable and hopefully a drawing can reach back and forwards.

Developing Ideas

The study for Satellite (2016) is color pencil and in a shot color.

Satellite Study

Because the actual drawing is virtually the same it occurred that another iteration could be made. To make the only actual object become more like a character in a story you could change size or distance of the object, which is the solitary cloud.

Study for Satellite Two

Some drawings take a lot of edits. Dissolve for a long time doesn’t have a focal point. May be the eye-like cloud in the center, but it feels more like a subconscious drawing. A lot of these drawings really depend on rendering. Like several pieces here, this one uses Alaskan graphite, which is from the Kigluaik Mountains near Nome, Alaska.

I want to make Native drawing with materials that are geographically centered in Alaska, my Native land. For me it grounds the pieces in a place I lived in during my formative years, but I’m not sure how conceptual you could call that. What I hope is that what is unspoken about these drawings can also be somehow felt, hopefully through the materials it’s made with, too.

Graphite One has kindly shared the graphite that this and other drawings are made with.

Dissolve. 2023.

Being Native and a College Graduate

It isn’t uncommon to realize your art changes during and after college, but for Alaska Natives it can take on new meanings several times. Visual artists keep making work after college; however, it didn't occur to me to center my Native experience until my last year of college. Recalling the person, you were before that (and after) becomes a way of looking back at your past and what you may have meant to other people.

For me moving out of Minneapolis- where I lived for most of my life- and graduating in Chicago, was such a large part of that change. Of course, we are different year-to-year, however for me it meant a lot to meet so many other artists. Meeting Pascha Nierenhausen, a Quechan and Lakota artist, also made me realize how few Natives there are in college. Despite that, you still meet people who are doing the same thing you are, learning to curate, or even just using audio as your medium. Everyone is generally doing the same thing you are trying to do.

From the beginning and as an influence, Nierenhausen had introduced artwork that centered as Native art. For that and other reasons my art has changed a lot. Painting was something I started at the University of Minnesota, but at SAIC I returned to drawing.

My work doesn’t have whales or Native villages. This may highlight form as a problem in work that doesn’t show any Alaska Native images. However, to me it could become necessary to show how differently an art object can be read as Native. Through my own decisions, my upbringing and education, societal changes, or a combination of several, my work seeks to change how Native art is understood as Native, what that means to me and to an audience that has the chance to see it.

College showed me what the art world was like, how art is considered part of a every current dialogue. What was missing from so much of the art I learned about was any Native artists. There weren’t any at the galleries I went to, and as far as I recall there weren’t Native artists featured in a lot of classes. Perhaps a large part of that was that they remained largely unknown. That has changed too since #MeToo, the election of Obama, and other changes.

Alaska is a source of influence for me. Now that there have been more Native artists featured in the Whitney Biennial, publications such as Art In America, and large metropolitan galleries, this offers a larger framework to bridge what has previously been an obstacle to what can now be seen as a possibility: publicly visible Native Contemporary art. It is a better chance than ever for Natives to make a statement.